6 minutes

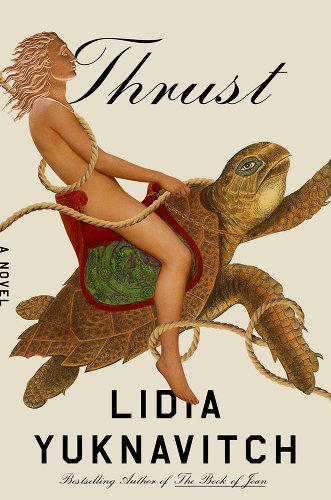

Lidia Yuknavitch, Thrust

This book is for Miles Mingo, sun of my life. And for every child who will cross the threshold next, every kind of body and soul, every orphan and misfit, every immigrant and refugee, every gender imaginable, every lost or found beautiful being looking for shore, home, heart. That space between child and not: imagine it as everything. Hold it open as long as you can. You are right. You are the new world.

– Lidia Yuknavitch

Thrust by Lidia Yuknavitch @ Bookshop

Quotes

To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it “the way it really was.” It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger. - WALTER BENJAMIN

We were the impossible possible voice of bodies.

We wondered what story would emerge in place of emancipation, now that the chains were hidden.

From the position of the stop signs and fire hydrants, he could tell he was about halfway home. He aimed at cracks with his scuffed-up shoe: five, six, seven. If he hadn’t been looking down and concentrating so hard on the geography of the sidewalk, he probably would have missed it. The thing on the ground. Or stepped in it.

I am still haunted by the concept of freedom. I wonder, who on earth has ever known freedom? Oh, we claim it for ourselves often; as peoples and nations and individuals, we’ve inflicted countless barbarisms and tortures upon our fellow man to prove that some of us have it by god, and others do not, will not, but that’s not really freedom, is it? That is power. Ugly. Degenerate. Reprobate unless it has a corresponding release. Otherwise it gets cocked up in a body.

You want to give form to freedom, you say-the abstract idea of freedom? Let me tell you about freedom. Freedom is the body of a woman. The devouring, generating paradox of her body. Every law every aspiration every journey a man takes fails in the face of ber body. The women I know who sell their bodies for cash in this gleaming city are separated from the bourgeois married women by a membrane thinner than a scrotal sack. To wit: by law, any woman who has premarital sex is a prostitute. Our bodies-and by bodies, I mean our sex, our cunts, the sources of our reproductive worth are held by our legislators at a level just above livestock, a fact I know you tire of me restating. Yes, it’s true, women have and will always provide sex to men for any number of reasons: for food, for clothing, for entertainment, for housing, for a fiction of respectability or a fiction of whore-gasm. The commercial direction of the act, the production of the sex worker as part of the workforce, unveils the tensions and falsehoods embedded inside your precious word and fiction of “freedom." Freedom? We need a new fiction that begins with the poor. The hungry. The filthy and the obscene. Not the exhausted bodies that bear the weight of a society’s growth-women who bear children bat women who carry the surplus, the spent seed that adds no number to the population. Women who emerge from crossdressing men. Hermaphrodites and lesbians, nádleebi, lhamana, katoeys, makhannathun. Look them up, dearest, if I’ve confused you. Bring me Kalonymus ben Kalonymus, Eleanor Rykener, Thomasine Hall. Bring me Joan of Arc. Bring me Albert Cashier and James Barry, Joseph Lobdell and Frances Thompson.

As for the children from Room 8, we invented a private ritual for our journey. Each child held an apple in a half bite in their mouth. They stood in a great circle, all apple-mouthed. Then, on my com mand, each child knocked the apple from another’s mouth, so that the rest of the apple flew away, leaving only a small bite between their teeth. The force of knocking the apple from another’s mouth a reminder that anything a woman or child wants in the world will be forcefully taken from them unless they bite down-an animal truth.

So maybe the stories in my head are from her, or from the people we met there, or maybe they’re mixed up with stories my father told me. Or maybe the stories just keep multiplying, accumulating from my own witness of animals and trees and objects and water, repeat ing and repeating in waves. So know this: When I say I remember my mother, I could mean anything. When I say once I had an infant brother, I could mean any thing.

So many stars. Constellations that seem to come apart for a moment, then reunite, then part again. I close my eyes and reopen them. Suddenly, the stars seem to stitch new stories across the sky I put the toddler in the hull of a boat. I wrap a blanket around this child and ask the boat to hold it in its belly. I speak a prayer for protection up to the white whale stars in the sky. Then I dive down after my father

Her shoulders underneath my height made me want to touch them. I could feel her beauty in my jaw. No, not beauty like you’re thinking of it in other women. It was more a beauty from the inside. A beauty screaming.

I go to work around eleven at night and I finish around six in the morning. I guess you could say we keep the buildings clean so that others can achieve the great work of the nation… but we’re the ones who take care of all the shit. It’s almost like we’re an entire undercity. No tell ing what goes on above us. Like another history. Another world. Tisha’s brother ascended, though. He worked for the Capitol Police. He no longer works there or anywhere. There’s a cost to ascension.

Laisvé continues her narration, delivering information, objects, ideas “The habitat power supplies all check out-ocean, sun, wind… But we need to talk about the underwater farms and the pods. The labs and medical bays are solid, but the dormitories are… well, they’re kind of ugly. They can’t be ugly. Living underwater should feel like the dreams children have. We can’t have ugly.” She dries her hair. “The moon pool is perfect, though." “Why is it called a moon pool?” Indigo’s question folds into Laisve’s monologue as they walk back into the habitat, painted indigo, cerulean, aquamarine, and midnight blue. “Good question. Because, on very calm nights, the water under the rig reflects moonlight. Like the ocean is glowing open,” Laisve says, “like a perfect portal. You know, portals are everything. Even a single thought can be a portal. A single word. You know, the way poetry moves.”

But Mikael tends to think everything turns on imagination — the smile on a worker’s face at the end of a day’s labor building a future anyone might inhabit, or the face of a child who believes in some thing larger than themselves, a beauty held like a world, a marble, in your hand. And liberty.